Event-driven: what to consider?

Don't build an event-sourcing framework

In this blog, I’ll go over what to consider when your organization wants to work in an event-driven manner. I’ll go over event-storming, ubiquitous language, bounded contexts, event sourcing, CQRS, event catalog and what to consider technically when you want to work in an event-driven way. Some of the topics might not be needed to implement event-driven in your organization.

What is event-driven?

Event-driven architecture (EDA) can distribute work amongst teams by providing a loosely coupled, asynchronous communication model between different components or services in a system. To enable asynchronous communication you would need a message bus. Examples of these products are Kafka and Pulsar. This works well for larger organizations where multiple teams are working on one or several products at the same time.

In an EDA, events are used to trigger actions or updates in various parts of the system, rather than relying on tightly-coupled point-to-point communication (RPC via for example REST/gRPC). This allows each team to build and maintain their independent microservices, which can be more easily scaled, and modified as needed.

Teams can work on different services or components in isolation, and the system can still function as a whole as long as they conform to the agreed-upon event schema and protocols. This can enable more rapid development and deployment of new features, as well as improved fault tolerance and scalability.

Additionally, EDA can provide better visibility and traceability of system behavior, as each event can be logged and tracked throughout the system. This can help teams quickly identify and troubleshoot issues, and provide more accurate reporting and analysis of system performance and behavior.

How to do it?

There are several techniques involved like

- Discover the (sub) domain with engineers and stakeholders with event storming

- Creating a ubiquitous language

- Segregating teams and responsibilities by bounded contexts

- Creating producers of events by event sourcing

- Segregating read and write databases by applying CQRS

- Discover events from other bounded contexts by using an event catalog

- Consider the technical requirements

What is event storming?

During a collaborative workshop, participants from various disciplines gather together to create a visual representation of a system or process using sticky notes and markers. The process starts by identifying the events that happen in the system and then organizing them in a timeline. These events can be anything that changes the state of the system, such as user actions, system responses, or external events.

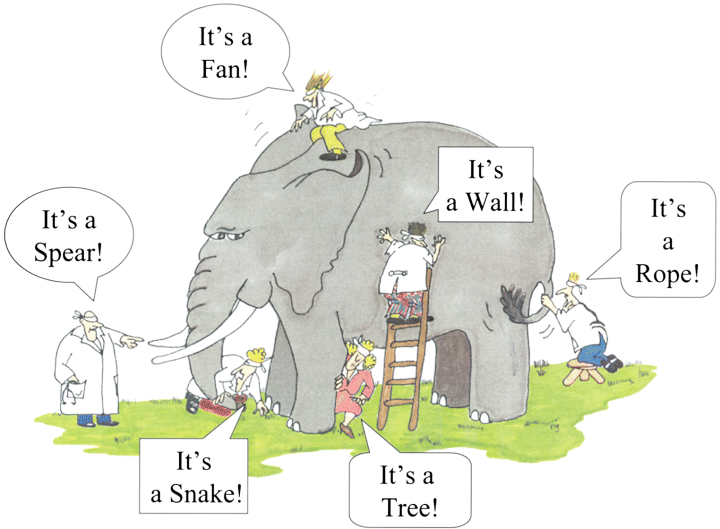

The Blind Men and the Elephant is a parable from India that has been adapted by many religions and published in various stories for adults and children. It is about a group of blind men who attempt to learn what an elephant is, each touching a different part, and disagreeing on their findings. Their collective wisdom leads to the truth.

Event storming is an iterative process that allows participants to continuously refine their understanding of the system as they work through different scenarios and edge cases. It helps to identify potential problems and dependencies, as well as opportunities for optimization and improvement.

What is a ubiquitous language?

The goal of ubiquitous language is to create a shared understanding of the domain, which helps to avoid misunderstandings and ambiguity when discussing business processes, requirements, and solutions. The development of a ubiquitous language is an iterative process that involves continuous collaboration and refinement. The language is developed through discussions between domain experts and developers.

What is a bounded context?

A bounded context is used to define a clear boundary around a specific domain, which allows teams to manage complexity by breaking down the system into smaller, more manageable parts. Within a bounded context, there is a shared understanding of the domain-specific language, concepts, and rules that govern that part of the system.

The concept of a bounded context helps to ensure that different parts of a system are not tightly coupled, which can cause problems such as misunderstandings, duplication of effort, and conflicts. Instead, each bounded context has its own distinct language and models, which are tailored to the specific needs and requirements of that context.

What is event sourcing?

Event sourcing is a software architecture pattern where instead of storing the current state of an application in a database, the application’s state changes are recorded as a sequence of events. These events are then used to reconstruct the state of the application at any point in time. It’s like a cassette tape.

In an event-sourced system, every change to the application’s state is represented as an immutable event object that captures the essential details of the change. These events are stored in a log-like structure, called the event log, which keeps a record of all the events that have occurred in the system.

Whenever the current state of the application needs to be queried, it is computed by replaying all the events in the event log, in the order they occurred, starting from an initial state. This process is called event replaying.

Producing events is usually handled by a concept known as an aggregate. An aggregate is a cluster of related objects that are treated as a single unit for data consistency and transaction management. An aggregate is defined by a root entity, which is responsible for maintaining the consistency of the entire aggregate. All modifications to the aggregate must be performed through the root entity.

In Haskell you can define the behavior of an aggregate using pure functions. This is often known as the brain of the aggregate. There are implementation details like schema evolution, single-writer, sharding and storage I’ll cover later.

class Aggregate s where

data Error s :: *

data Command s :: *

data Event s :: *

execute :: s -> Command s -> Either (Error s) (Event s)

apply :: s -> Event s -> s

seed :: s

data User = User {

name :: String,

email :: String

} deriving (Show)

instance Aggregate User where

data Error User = NotAllowed

| TooShortUsername Int Int

| EmptyUsername

| EmptyEmail

deriving (Show)

data Event User = NameChanged String

| EmailChanged String

deriving (Show)

data Command User = ChangeName String

| ChangeEmail String

deriving (Show)

_ `execute` ChangeName n = NameChanged

<$> validate notEmpty EmptyUsername n

<* validate (lengthBetween 4 8) (TooShortUsername 4 8) n

_ `execute` ChangeEmail e = EmailChanged

<$> validate notEmpty EmptyEmail e

state `apply` NameChanged n = state { name = n }

state `apply` EmailChanged e = state { email = e }

seed = User "" ""In this case, for every aggregate you define specific type-families for Error, Command and Event. Note that execute and apply are there 2 most important pure functions you need for event sourcing. The execute function validates the incoming command and either throws an error or an event. The apply function will apply the event to the current state. This can be used after applying the command or when reconstituting the state from an event log.

What is CQRS?

CQRS (Command Query Responsibility Segregation) is a pattern that separates the processing of commands (which change the state of the system) from the processing of queries (which retrieve data from the system).

The commands are processed by the command handlers which are implemented using event sourcing, while the queries are processed by databases that allow fast reads. This can lead to a more efficient and scalable system, as well as improved performance and maintainability.

Events are processed by event handlers, also known as projections which typically consume a message bus like Kafka or Pulsar and project these events to a specific read model. Commands typically require strong consistency and transactional processing, whereas queries often require fast response times and denormalized data structures.

The caveat of CQRS is that the read-side is eventually consistent. This means that processing a command does not result in an immediate update to the read-model. It might take a little bit to update it, hence eventually consistency. This is in a lot of cases not a problem, however. Also, a thing to consider is that there is no guarantee that the event will be delivered once. Therefore processing events should be idempotent. If an operation is idempotent, performing it multiple times will produce the same result as performing it once.

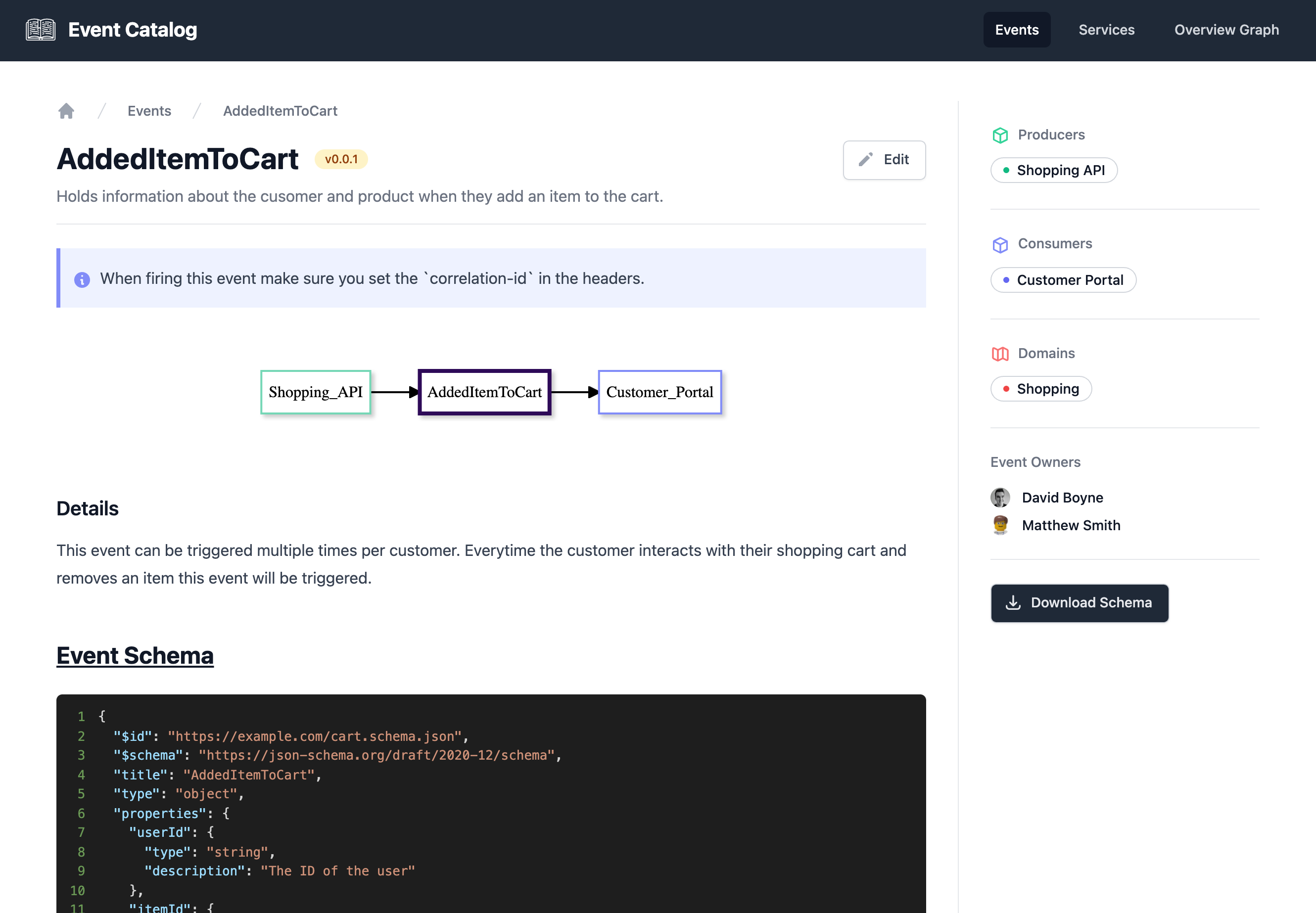

What is an event catalog?

Over time our Event-Driven-Architectures grow and it can become difficult to discover and understand our events, schemas, producers, consumers and services.

An event catalog is a collection of all the events that can be produced or consumed by a system, providing a reference point for developers to understand the types, schema, source, and consumers of events. It helps ensure consistency and streamline the development of event-driven systems.

Consider technical requirements

While we’ve only tipped a little bit on the technical side at the event sourcing a part, it’s now time to consider the technical requirements.

Actors

An aggregate is also known as an asynchronous boundary and this exactly matches the semantics of an actor.

Actor programming is a paradigm for building concurrent and distributed systems based on the concept of actors. Actors are independent units of computation that communicate with each other by exchanging messages, and each actor has its local state and behavior.

The messages sent to the actor are Command messages. Internally the actor could rebuild its state by replaying all the events. If the event log for a specific aggregate becomes large you need snapshotting to compress the state at a certain point and go from there.

Each aggregate instance will get its actor. Where an instance is for example user ‘John’ and ‘Mark’. Both are two actor/aggregate instances that will have their message queue/mailbox to process incoming commands. To distribute a lot of actors in your system you’ll need sharding.

Scala has options like Akka and Kalix. Kalix builds upon Akka and abstracts away all the operational complexity of running an event-sourced system. In Rust, I’ve come across Coerce which seems to do the same what Akka does. I haven’t tried it yet, but it looks promising.

Sharding

Sharding in actor-based programming is a technique used to partition actors across multiple nodes or servers in a distributed system. This is similar to database sharding, but instead of partitioning data, the actors themselves are partitioned.

Sharding is often used in actor-based systems to improve scalability and performance by allowing the system to handle larger numbers of actors and messages. By distributing the actors across multiple nodes, each node can handle a smaller subset of the total actor population, which can help to reduce contention and improve throughput.

Both Akka and Coerce support sharding.

Event payload and evolution

As new features are added to the application, or new types of events are introduced into the system, the underlying event schema may need to be updated to accommodate these changes. This can involve adding new fields to existing events, creating new event types, or modifying existing events to include additional information.

Schema evolution in event-sourced systems can be a complex process, as it involves ensuring that existing events are still valid and can be replayed correctly after the schema changes are applied. To manage this, it is common to version the event schema, so that different versions of the schema can be used for different events.

It is also important to consider the impact of schema changes on downstream systems that consume the event stream. For example, if a new field is added to an event, downstream systems that consume that event may need to be updated to handle the new field.

Avro is a format for encoding/decoding application data to a binary format while using a schema. The schemas are stored in a schema registry which can be used to enforce forward and backward compatibility. By using Avro in conjunction with a schema registry you can enforce compatibility while also having a compact and performant format for storing events. A format that is compact and performant will become important when your system grows and the size of the event log becomes too big if you would use a format like JSON.

Storage medium

While we’ve partitioned the actor system via sharding, it is also important to keep in mind that the database you use can handle the write load. Postgres and MySQL can work fine for certain workloads. When you write load increases you might consider Cassandra.

Apache Cassandra is an open-source, distributed NoSQL database management system designed to handle large amounts of data across many commodity servers, providing high availability with no single point of failure. Cassandra is known for its ability to handle very large amounts of data and for its high write-throughput, making it a popular choice for big data applications.

Conclusion

When your organization goes event-driven it introduces an alternative way to model and work with your systems. You might already work with microservices where multiple teams maintain a set of microservices. While this already enables a way to partition work to be done it has some caveats in terms of resiliency and efficiency. Assuming you are calling other microservices via RPC, this approach is brittle due downtime of another microservice. Also, the other team might implement a specialized API for your use case which is inefficient. This leads to the creation of a distributed monolith. While in some cases monoliths are more efficient (see AWS blog) and a good tool to prototype new ideas. There is a tipping point where you want to shift the model of working.

Breaking down significant events with event storming with the whole team, from developer to stakeholders makes the whole team aware of how the system will or should work. This also leads to a ubiquitous language, so the whole team knows conceptually what you talking about. When an organization is larger there might be multiple teams, which should be split by a bounded context.

From a technical perspective, event-sourcing and CQRS are natural patterns that emerge while working event-driven model. There are a few things to consider like actors, sharding, event format, schema evolution and storage medium. I would recommend sticking with a library or framework for most of these parts.

The only exception would be the brain of an aggregate, since these are pure functions that (might) form a Finite State Machine (FSM) it’s easier to decouple this from the actual library/framework. This would enable easy tests since you test pure functions. There is no real need to test the actual framework because it’s already been tested. A black box test which tests the whole system from the outside would be a good additional test suite,

I hope by reaching the end of the post you’ve concluded that event-driven architecture has advantages and challenges for organizations. If you need any help implementing it, let me know by dropping me a message.